Har du noen som helst ambisjon om å lykkes som investor, er investorbrevene til Nick Sleep og Qais Zakaria høyest anbefalt lesning.

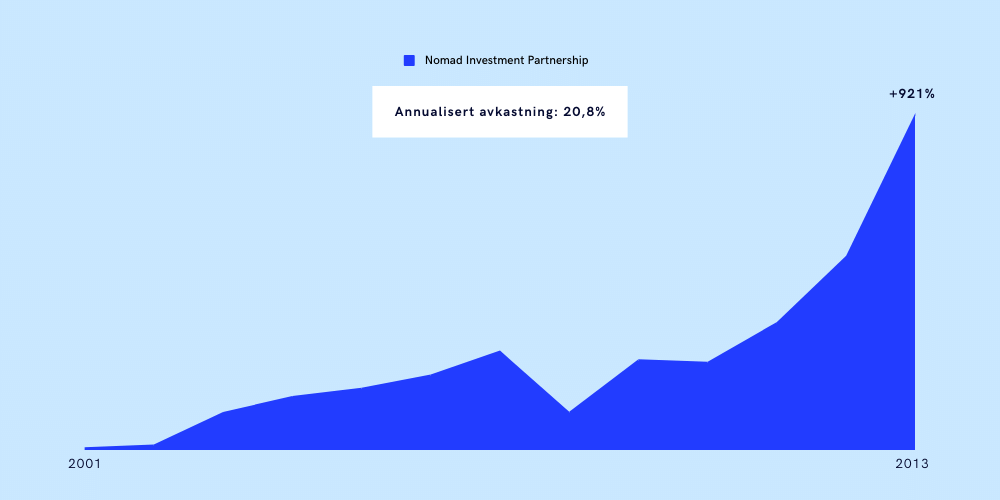

I perioden 2001 til 2013 oppnådde de en annualisert avkastning på 20,8% før kostnader (18,4% etter kostnader). I samme periode ga MSCI World Index en annualisert avkastning på 6,5%! De knuste markedet.

Og samtidig som de knuste markedet, forklarte Nick hva de så etter og hvordan de identifiserte de beste investeringene i sine investorbrev.

Etter å ha lest investorbrevene fra A til Å, og tatt notater som en student i eksamensmodus med 500mg koffein og 100mg ritalin injisert rett i blodåra, har jeg samlet 5 viktige lærdommer jeg bet meg merke i.

Disse er bare dråper i havet, så jeg gjentar: har du noen som helst ambisjon om å lykkes som investor, les investorbrevene til Nick Sleep og Qais Zakaria.

Favoritt sitat:

Good investing is a minority sport, which means that in order to earn returns better than everyone else we need to be doing things different to the crowd. And one of the things the crowd is not, is patient.

Nick Sleep

Lærdommer:

- Den dyreste feilen du gjør er å selge for tidlig

- Du må klare å identifisere de underliggende driverne for langsiktig forretningssuksess, og være tålmodig

- Tiden øker avkastning og reduserer risiko

- Fokuser på analysen, resultatet tar seg av seg selv

- Ha en liste hengende på kontoret over fantastiske selskaper (vær klar til å utnytte feilprising)

Den dyreste feilen du gjør er å selge for tidlig

Fra investorbrevet i 2005:

So, for example, the biggest mistake an investor can make is to sell a stock that goes on to rise tenfold! Not from owning something into bankruptcy. But that’s what everyone thinks, at least judging by the questions we get from clients. Only last week we got questions about our holding in Northwest Airlines rather than the sale of Apple earlier this year. But selling Apple has cost us more. People look at actual costs, not opportunity costs, and what did we say about over-weighing the vivid evidence? And if you understand that, and you understand probabilities, then you’ll know Northwest wasn’t worth calling us about.

Fra investorbrevet i 2007:

After the doubling in the share price and the weighty resultant position in the Partnership it would be easy for Zak and me to claim victory, high five, and sell our shares in Amazon. However, the high weighting makes sense given our understanding of the destination of the businesses and the probability of reaching that destination. In previous Nomad letters we have argued that the biggest error an investor can make is the sale of a Wal-Mart or a Microsoft in the early stages of the company’s growth. Mathematically this error is far greater than the equivalent sum invested in a firm that goes bankrupt. The industry tends to gloss over this fact, perhaps because opportunity costs go unrecorded in performance records. For example, our greatest error was the sale of Stagecoach (which has risen ever since sold), not the purchase of Conseco! We wonder, would selling Amazon today would be the equivalent mistake of selling Wal- Mart in 1980 (a similar time period after both companies’ IPOs)?

Når du investerer i aksjer, så er ikke den dyreste feilen å investere i et selskap som går konkurs, men å selge en fantastisk investering for tidlig.

I den første situasjonen kan du, hvis du er skikkelig uheldig, tape maksimum 100% av investeringen. I det andre derimot, så kan du tape mye mye mer. Poenget hans er at du må vurdere alternativkostnaden.

Ved å selge en investering som øker 10x etter du har solgt, så har du i realiteten tapt differansen mellom det du investerte pengene i etter du solgte og det du gikk glipp av som følge av salget.

Han viser til sine egne investeringer i Stagecoach og Conseco for å illustrere dette poenget. Mens han tapte på investeringen i Conseco, så tapte han vesentlig mer på salget av Stagecoach – til tross for at de solgte i pluss, siden den økte mer i etterkant.

Identifiser de underliggende driverne i selskapet, og vær tålmodig

Fra investorbrevet i 2009:

Investors see the information (on conference calls they cheer “great quarter, Wal- Mart”) but, in our opinion, they incorrectly weigh the information. It could be argued that lots of things had to go right for Wal-Mart to grow for forty years. That is certainly true but, at its heart, a very few simple things really mattered.

In our opinion, the central engine of success at Wal-Mart was a thrift orientation fueling growth with the savings shared with the customer. The culture of the firm celebrated this orientation and reinforced the good behaviour. This is the deep reality of the business (utheving tilføyd). This should have had the greatest weighting in the minds of longterm investors even if other things looked more important at the time. Instead, investors may place too much emphasis on valuation heuristics, or margin trends, or incremental growth rates in revenues or any of the list above, but these items are transitory and anecdotal in nature.

Han påpeker gjentatte ganger at markedet er for opptatt av det som skjer her og nå – om selskapet slo forventningene eller om marginene er opp eller ned det siste året. Investorer glemmer, eller undervurderer, de underliggende driverne for langsiktig forretningssuksess.

De underliggende driverne kaller han for selskapets deep reality og DNA. Og han mener at hvis du klarer å identifisere disse, og være tålmodig, så er det stor sannsynlighet for at du vil lykkes i markedet. Siden den gjennomsnittlige investor har et svært kortsiktig fokus, er det en fordel å være langsiktig.

Fra investorbrevet i 2009:

The trick, it seems to us, if one is to be a successful long-term investor, is to recognize the sources of enduring business success, get in early and own enough to make a difference.

- Deep reality handler om å se utover overflatiske data og trender – for eksempel at driftsmarginen faller fra et år til et annet – for å forstå de dypere, ofte skjulte kreftene som driver selskapets langvarige suksess.

- Med DNA mener han de grunnleggende og uforanderlige egenskapene til et selskap, som dets forretningsmodell, ledelseskvalitet og bedriftskultur.

Han gir et eksempel med Walmart:

Han identifiserte Walmarts dype virkeligheten til deres dedikasjon til sparing og effektivitet, noe som ikke bare ga dem en konkurransefordel, men også formet kulturen i selskapet. Dette prinsippet om å spare, og deretter dele besparelsene med kundene – gjennom lavere priser – skapte en syklus av vekst og kundetilfredshet som var vanskelig for konkurrenter å matche.

En av Nick Sleep’s kronjuveler er investeringen i Costco Wholesale (COST). Han identifiserte flere viktige aspekter ved Costco som mange andre overså. For eksempel fokuserte markedet negativt på lave marginer, noe Nick mente var en bevisst strategi. I 2004 forklarte Nick 3 feilvurderinger markedet gjorde:

Fra investorbrevet i 2004:

So, what heuristics do investors incorrectly apply to Costco (why might the shares be mis-priced?).

Heuristic One (utheving tilføyd): “the company has low margins” (net profit margin is 1.7%, compared to Wal Mart at 3.6% and Target at 4.2%). True, but that’s the point. The firm is deferring profits today in order to extend the life of the franchise. Of course, Wall Street would love profits today but that’s just Wall Street’s obsession with short term outcomes.

Heuristic Two (utheving tilføyd): “it’s expensive at 24x earnings”. Really? Net income is a small residual, as discussed above. The firm could earn Wal-Mart margins by taking pricing up a little, in which case the firm would be on 11x earnings, but would it be a better business as a result? We think not, if it allowed the competition to catch up.

Heuristic Three (utheving tilføyd): “Costco has a cost problem”. Costs have risen as a percentage of revenues in the last few years due to the expense of a warehouse and distribution system associated with the next phase of the firm’s growth and the cost of employee benefits and insurance, especially in California. This has people fooled who really should not be. At the annual general meeting for an investment company that we hugely admire, the investment firm’s founder (and industry hero) was asked by a client why their holding in Costco was just 1% of the fund, especially when they have a reputation for portfolio concentration. The answer given was that of the firm’s three constituencies (labour, customers and shareholders) the first two had been ascendant. This sounds nice and neat, but the phenomenon is cyclical: labour are “happy” according to Sinegal, Costco’s founder and CEO, incremental stores will leverage fixed costs, and in the letter to shareholders Sinegal describes costs as “unacceptable”. In short, they are on to it. Our investment hero was mistaken, by about U$20 per share so far, or a gain of 65%.

I 2006 forklarte han det samme fenomenet – at markedet mistolker situasjonen på grunn av et kortsiktig fokus – med Amazon.

Fra investorbrevet i 2006:

How do we know we are taking a different view to the crowd?

A clue can be gleaned from the period that other investors typically hold the shares of the companies in the Partnership. If Berkshire Hathaway (US), Jardine Matheson (Hong Kong) and Next Media (also Hong Kong) are excluded (these firms are in a class of their own due to either stock illiquidity or investor education) then other investors hold stocks in our portfolio for on average twenty weeks. We expect to own shares for around two hundred and sixty weeks!

So, what is going on?

It seems to us that most investors look at the accounting outputs of a company (the reported financial data) as a guide to near term price movements and play the market accordingly. As stated in the investment objective section of the Nomad prospectus our goal is to “pass custody (of your investment) over at the right price and to the right people”. That’s what investing is. Zak and I concentrate on a deeper reality: the inputs to future value moves. Our peers are trading shares at the short end of the equity yield curve where the competition is the greatest, and we are investing at the long end where competition is the least.

We respond to completely different stimuli. Take for example the current controversy at Amazon.com.

Last year the company reported free cash flow of just over U$500m, indeed it has been around this number for the last few years. What is important is that the U$500m is after all investment spending on growth initiatives such as capital spending, but also research and development, shipping subsidy, marketing and advertising and price givebacks.

The firm has been investing in these items today to grow the business in the future so that free cash flow in years to come will be meaningfully greater than it would be otherwise.

By our estimates these discretionary investments, over and above that required to maintain the business, are in the region of a further U$500m, excluding the price givebacks. This is our subjective assessment of the discretionary investment spend and implies that management could, if so inclined, cancel the discretionary growth spending and instead return around U$800m per annum to investors after taxes. An operation that was able to produce cash flow on such a basis might be worth U$10bn or so, and along with Amazon’s other assets would imply a share price of around U$26.

In valuing the business at these prices, as occurred last summer, investors are saying to Amazon management “your growth spending has no value, you may as well turn yourself into a cash cow”! This is an odd statement to make for a business growing revenues in excess of twenty percent per annum.

Tiden øker avkastning og reduserer risiko

Tiden i seg selv er verdifull i aksjemarkedet. Hvorfor? Fordi det er enklere å forutsi selskapets fremtid flere år fremover (basert på selskapets strategi, investeringsvalg og verdsettelse), enn det er å forutsi hvordan resultatet ser ut neste år.

Dermed vil tid både øke avkastning og redusere risiko, i følge Nick.

Fra investorbrevet i 2006:

Good investing is a minority sport, which means that in order to earn returns better than everyone else we need to be doing things different to the crowd. And one of the things the crowd is not, is patient.

Readers of our letters (there must be some) may be familiar with the notion of the equity yield curve, and our thoughts were covered in an interview for the Outstanding Investor Digest (reprints available upon request, do ask Amanda) a few years ago. (In brief, the equity yield curve is a concept that argues that patience has a value, and that returns increase with time in the equity market as they do on a normal bond market yield curve).

In the bond market the higher yield is there to compensate for the increase in risk that the principal will not be repaid, or that the principal may be devalued by inflation. That is not how it works in the equity market: in our opinion business outcomes can be more predictable several years out than they are in the near term. For example, we have no idea where the market will end this year but given corporate strategies, capital allocation and starting valuations, I think we have some idea of how our companies will evolve over the next few years.

In other words (at this point economics students may wish to cover their ears) the return from investing in shares can be both increased and de-risked by time. There may be a blind spot in academia as the overwhelming methodology for research in Economics has been to take observations over short time periods, as if cause and effect sit on top of each other.

Habits can take years to form. What, we wonder, would academics have to say of Coke’s century long advertising program and the eventual establishment of the World’s most valuable brand?

Som et eksempel forklarer Sleep hvordan forretningsmodellen til Costco førte til at fremtiden til selskapet var enklere å forutsi enn mange andre.

Fra investorbrevet i 2005:

To repeat: “what you are trying to do as an investor is exploit the fact that fewer things will happen than can happen”. That is exactly what we are trying to do. We spend a considerable portion of our waking hours thinking about how company behaviour can make the future more predictable and lower the risk of investment. Costco’s obsession with sharing scale benefits with the customer makes that company’s future much more predictable and less risky than the average business and that is why it is our largest holding.

Les om forretningsmodellen Scale Economics Shared, som Nick Sleep mente var en av få forretningsmodeller som virkelig fungerte over lang tid.

Fokuser på analysen, resultatet tar seg av seg selv

Nick var klar på at det er kvaliteten på analysen din som avgjør investeringssuksess du vil oppnå, men som han så elegant påpeker: du kan ikke styre når suksessen fra investeringen dukker opp. Det er utenfor din kontroll.

Derfor er det nødvendig å ha en følelsesløs tilnærming til resultatet (tilfeldigheter spiller inn over en kort tidsperiode), og heller fokusere på det som er viktig, altså kvaliteten av analysen.

Fra investorbrevet i 2003:

We were rather struck by some of the early Buffett Partnership letters in which Warren Buffett offers the following advice: return for a moment to the table above “and shuffle the years around and the compounded result will stay the same.

If the next four years are going to involve, say, a +40%, -30%, +10%, -6%, the order in which they fall is completely unimportant for our purposes as long as we all are around at the end of the four years”, as we, at Marathon [Nick Sleep og Qais Zakaria sin arbeidsgiver på dette tidspunktet], intend to be. “The course of the market will determine, to a great degree, when we will be right” (the sequence of annual outcomes), “but the accuracy of our analysis of the company will largely determine whether we will be right. In other words, we tend to concentrate on what should happen” rather than when it may occur.

Our preference is for results to be measured over a five-year time frame, and even this may be a little short compared to the average holding period of the underlying investments which is presently around ten years (inflated by a dearth of sales). In this context the short-term results remain just that, short-term, and you should be as indifferent toward results so far as the annual sequence in which they have occurred. A stoical disposition to short-term results is both the right way to think (never mark emotions to market) (utheving tilføyd) but it also prepares one for results that may be reasonable but are unlikely to be an extrapolation of the last two years.

Fra investorbrevet i 2007:

(…) the only real, long term risk, which is the risk of misanalysing a company’s destination.

Ha en liste med Super High-Quality Thinkers

På kontoret hadde Nick og Qais en liste med det de kalte super high-quality thinkers. Det var en gruppe med fantastiske selskaper, ledet av ærlige og kompetente mennesker som de betegnet som vekstmaskiner.

Fra investorbrevet i 2004:

In the office we keep a list of companies assembled under the title “super high-quality thinkers”. This is not an easy club to join, and the list currently runs to fifteen businesses. Entry is reserved for the intellectually honest and economically rational, but that alone is not enough. There are many companies that do the right thing when their backs are against the wall, and this list excludes those temporarily attending church. The anointed few are there because they have chosen to out-think their competition and allocate capital over many years with discipline to reinforce their firm’s competitive advantage. Good capital allocation takes many forms and does not necessarily require a firm to grow.

The Partnership’s successful investment in Stagecoach has been due to the firm’s shrink strategy, not its growth, although that may come in time. At National Indemnity (an insurance subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway), the firm’s ability to write insurance only when pricing is good and stand back when pricing is poor, even if revenues decline by 80% and remain depressed for many years, is a wonderful example of capital discipline and good capital allocation. After all, why grow if returns are going to be poor? However, surprisingly few companies have the strength to just sit it out, or shrink, as the pressure to grow is often overwhelming. The clamor comes from within the company (reinforced by poorly constructed incentive compensation), Wall Street promoters and short-term shareholders.

When faced with this barrage, the voice of the longterm shareholder often goes unheard. We ask companies with poor economics why they want to grow. And senior management, with their hands on our purse strings, look back at us incredulous at our line of questioning. It is just not that easy to resist the urge to grow, even if economic results look so so. The “super high-quality thinkers” are our best guess of those firms whose shareholders could abdicate [frasi] their right to trade stock (allocate capital themselves) sure in the knowledge that their capital will be well allocated for years to come within the businesses. This list is a group of wonderful, honestly run compounding machines.

We call this the “terminal portfolio”. This is where we want to go.

Super high-quality thinkers er et selskap hvor du som aksjonær kan frasi deg retten til å handle aksjer og samtidig være sikker på at de er i trygge hender. Dette minnet meg om Warren Buffets kjente sitat:

Only buy something that you’d be perfectly happy to hold if the market shut down for 10 years.

Warren Buffett

Problemet med mange av disse fantastiske selskapene var derimot prisen. De har en tendens til å forbli dyre, naturlig nok.

Fra investorbrevet i 2004:

Even though prices are generally high, the trick is to do the work today, so that we are ready.

Ved å gjøre analysearbeidet i dag og identifisere disse fantastiske selskapene, var de i stand til utnytte midlertidige feilprisinger i markedet med en gang de oppsto.

Til slutt

Nick Sleep og Qais Zakaria sin tilnærming til investering knuste markedet. De var alltid på jakt etter sannheten i en investering. Feil og dårlige investeringer ble gjerne fremhevet i brevene, med et mål om å lære og bli flinkere (og vise investorene sine at de ikke er perfekte).

Fra investorbrevet i 2007:

In investment terms, once lessons have been learnt, mistakes can be put on a price earnings ratio of one and the resultant, good behaviour on a ratio of more than one. In other words, mistakes become net present value positive.

Hvis disse 5 lærdommene vekket din interesse, bør du lese investorbrevene for deg selv. De er en gullgruve.